The Table Is Ours: A Starter Guide to Buying and Collecting Art

As buyers and collectors of the art and culture we produce, Black people can have a seat at that table — or build our own.

Written by: Briana Lynn Pickens

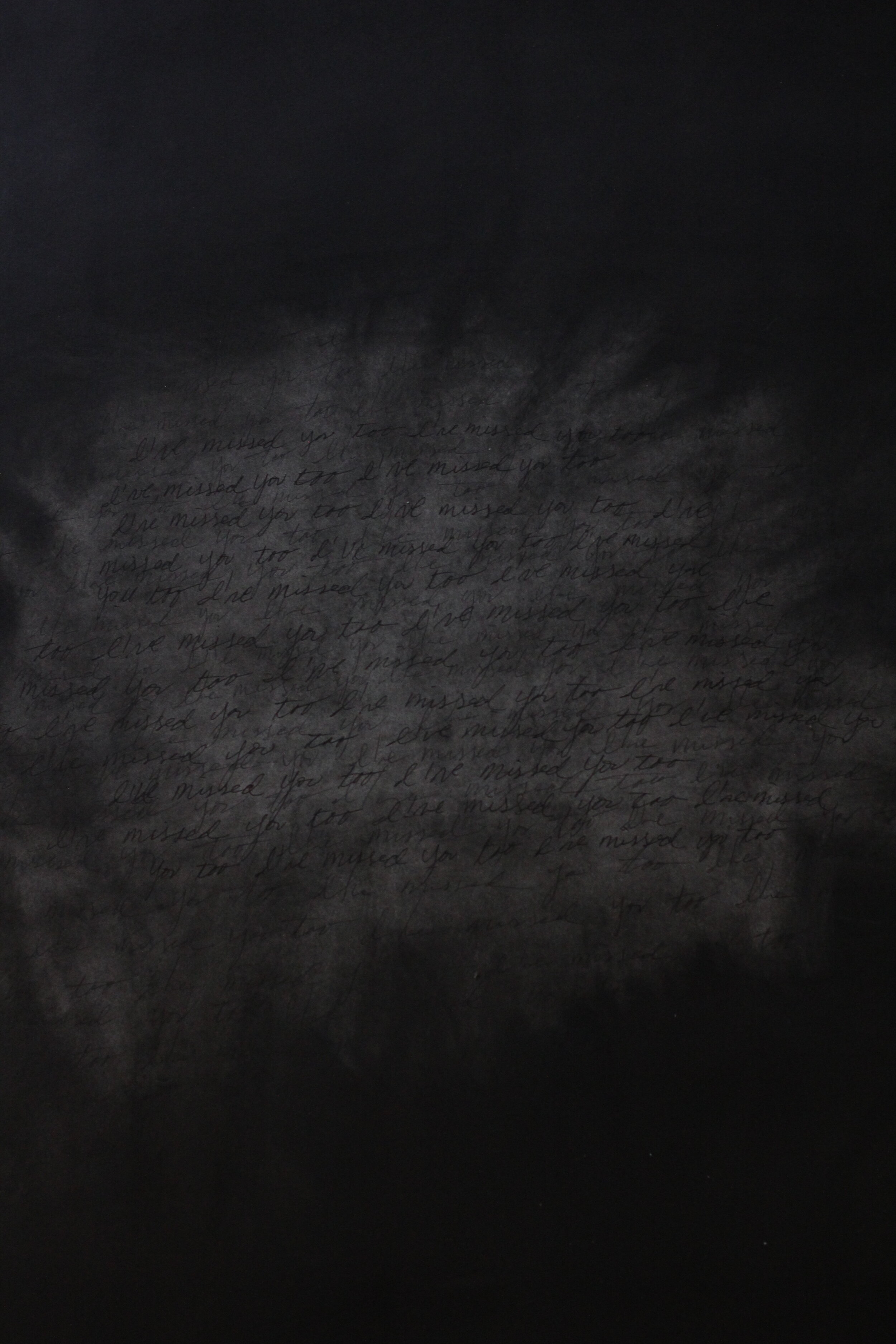

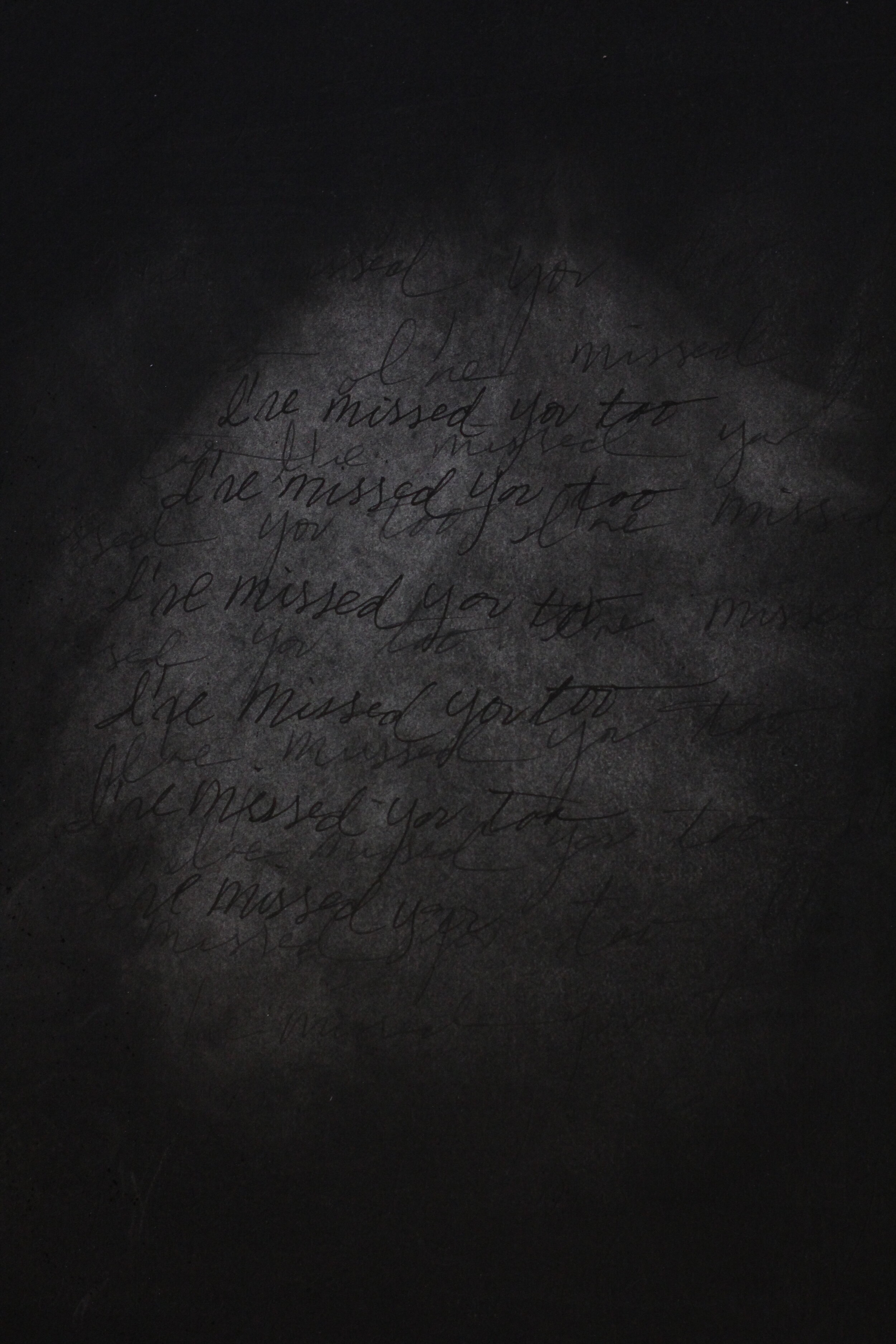

Cover Image: Nakeya Brown

June has cracked open every body and thing in america. Exhausted by racial insensitivity and violence in the art world — I’ve been thinking less about atonement and more critically about expressions of agency, specifically Black people as buyers and collectors of art.

How can Black people participate in the art economy?

How can the agency of Black artists be respected?

How can the art world be democratized?

How can a self-sustaining Black art market be realized?

As we talk about access and equity in the art world, I see the capacity for full participation by Black and people of color in the art market as essential. We need young, Black consumers and collectors inventing new models of ownership, new markets and an egalitarian art world.

So for anyone flirting with the idea, I wanted to share tools for self-education and empowerment around buying; realities about the cost of artwork; and general information that may make the process less intimidating.

Exhibition catalogs and art books are entry points…

...and cost-effective ways to get informed about Black artists and artistic practice. Exhibition catalogs are books produced for art exhibitions and available to the public. They may look intimately at a single artist or several artists if the exhibition is a group show. What’s cool about group catalogs is they can introduce you to multiple artists, likely with similar aesthetics or histories. Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power covers a period of Black American artistic production from 1963 to 1983. Books may also exist independent of exhibitions and center a theme and a variety of artists, like The New Black Vanguard: Photography Between Art and Fashion that features young photographers working at the intersection of art and fashion.

A monograph is a book that focuses on a single artist or body of work, like LaToya Ruby Frazier’s The Notion of Family, or Maïmouna Guerresi’s Inner Constellations, or the seminal Kitchen Table Series by Carrie Mae Weems — all favorites of mine for their quiet strength. A caveat is that publishing increases the value of an artist’s work. Published artists are often more established, and therefore expensive. But an advantage of art books is that they allow you to live with an artist’s work without necessarily owning the artist’s work, and the books double as art objects themselves.

You can visit bookstores at institutions that center Black artists like the Underground Museum in Los Angeles, the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco (MoAD), or the Studio Museum in Harlem. You can also visit any museum’s web archives to see their past exhibitions and available catalogs.

Evaluate your purse.

A friend once told me she didn’t think she had collector coin — so what is collector coin? In my opinion, a person with a monthly disposable income of at least $500 can afford to collect. If you’ve paid for a vacation, or bottle service, or frequent brunch, the cost is comparable. There are a number of artworks by emerging artists available under $1,000 or in the <$5,000 range. Financing options are available, as with any large purchase like a car or condo. An artwork is a similar investment, and its value appreciates, as opposed to a car that depreciates. Plus, its purchase directly supports Black artists. You can ask an artist or gallery directly about payment options, or have someone (e.g. an art consultant) negotiate on your behalf.

Buy prints.

They’re like second-base. A print is exactly that: a printed image — an image transferred onto another surface. Photographic prints, digital media prints, and “works of art on paper” are common. Prints often come in multiples called “editions” which alleviate the cost for a single buyer. So if an edition of 10 prints is worth $10,000, you get 1 print for $1,000. If you aren’t ready to commit to the cost or responsibility of a three-dimensional object, prints can familiarize you with buying and installation processes, as well as living with an art object. Try the powerful stills that address hair politics and traditions by Nakeya Brown, or the poetic and deeply human photography of Elliott Jerome Brown Jr.

Democratize ownership.

If you question the ethics of ownership, or the exclusivity of ownership, or the cost of ownership —split it. Buying an artwork as a collective then donating it to a museum or exhibition is a thing. The benefit is a seat at the table. This approach increases the number of stakeholders for that artwork, meaning more people can advocate on its behalf, and increases the number of Black influencers in the general market. Donation, or “gifting,” is also a strategy for supporting artists that work in time-based media (video, film, slides and audio) or other media that have unique properties or require more space, like Zakkiyyah Najeebah's intimate, conceptual documentation work, or Vaughn Davis Jr.’s vibrant soft sculpture.

All that said, where to buy artwork is still elusive. It can’t be bought from museums; galleries are secluded; and there’s no central “art marketplace.” Transactions often happen directly. But buying art is a thing where once you take the first step, the next steps reveal themselves. The most important step is getting informed. Black culture is commodified and Black people are excluded from having real agency or equity. As buyers and collectors of the art and culture we produce, we can have a seat at that table — or build our own.

Read more like this in The Money & Power Issue of our Journal

From learning when to scale back your budget to visualizing federal reparations, The Money & Power Issue tells the real story of Black wealth (or lack thereof) and reimagines a Black existence in America that imbues us with agency and perspective.