Bruce’s Beach: Diving into the Black Community’s Relationship with the Beach

Though we may not often see ourselves there, we still belong.

Written By: Jessica Frierson

Looking back on my twenty-something years, many of my cherished memories were at the beach: the first time I bonded with my niece at a friends and family picnic; the one and only time my friend and I won a beach volleyball tournament; the time my extended family rented a beach house for our family reunion. What I also remember from all of these memories is that we were the only Black folks around.

One of my favorite moments on the show Insecure is when Issa and her white co-worker supervise minority middle school students at the beach. When her co-worker asks why the students aren’t swimming, without missing a beat, Issa replies, “slavery.”

The beach is rarely, if ever, included in our dialogue about African American history. Many would argue that the beach is simply not a part of Black culture. After all, it is our past and our traditions that shape who we are as a people today. The relationship of the Black community and the beach is complicated – an episode of How to Get Away with Murder complicated. Several generations of African Americans do not know how to swim. For some, the thought of “dealing” with their hair is enough of a deterrent. Why should a place like the beach be a part of Black culture?

Because it was.

It is surprising to most to learn that there are several historic Black beaches along our country’s shores. About one hundred years ago in Southern California, Bruce’s Beach, now a part of Manhattan Beach, was an entirely different landscape.

In 1912, Willa Bruce purchased land from millionaire developer George H. Peck. Uncommon at the time, Peck did not restrict the purchase of incorporated land to only white men. Willa and her husband, Charles, expanded their two blocks by purchasing three additional lots – setting the foundation for the first Black beach resort in Southern California.

Yes, sis. We did that.

Bruce’s Beach was a safe haven in a world of segregation. With the development of the resort, the Black community in the area grew. More families bought property and more vacationers flocked to the area. Those on the resort could soak up the sun, relax in the bathhouse, and enjoy the dining club. It was a place where we could enjoy our own and be ourselves.

But soon enough, of course, there was opposition. The Black homeowners and vacationers were harassed and threatened in the community they built. In the early 1920’s, landowners were pressured to sell their properties for less than their worth. Eminent domain claimed other properties and the City of Manhattan Beach condemned Bruce’s Beach. The city attempted to lease the land – to a private individual – with the intention of creating a white-only beach. In 1927, the NAACP enacted a civil disobedience campaign that included a “swim-in.” Participants were arrested who then fought their charges and won. The decision to condemn the beach was overturned and the seaside opened again to the public – without restrictions. Over the years, the area has been renamed several times: City Park, Beach Front Park, Bayview Terrace Park and Parque Culiacán. The Manhattan Beach City Council restored the area’s original name in 2006, and the following year – eight decades after the NAACP’s campaign – they held a public ceremony in its honor.

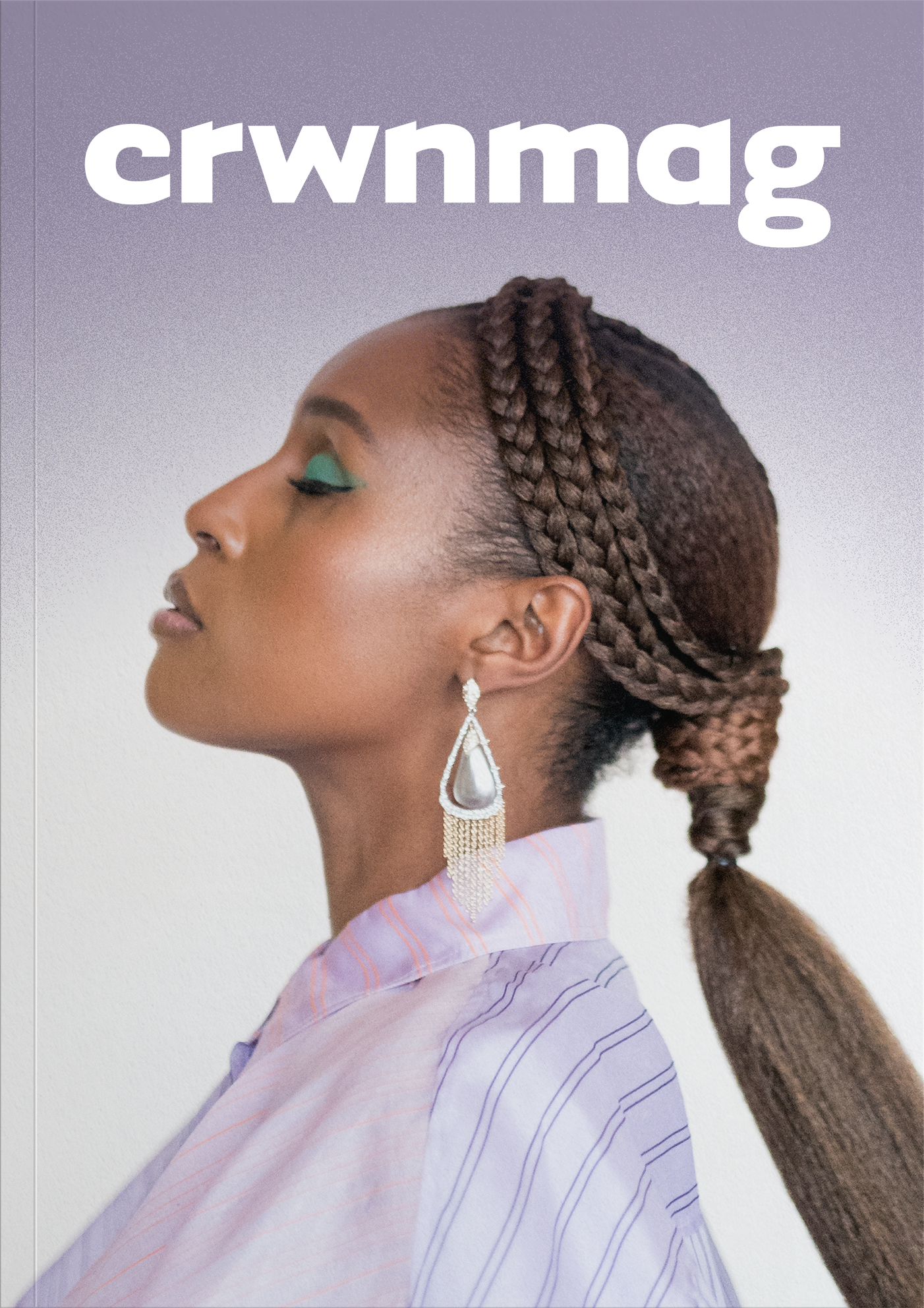

Pre-Order The Storytellers Issue with Issa Rae

Our founders sit down with the actress, writer and producer extraordinaire to discuss the upcoming season of Insecure, the importance of telling our own stories, entrepreneurship and more. Shipping in June.

It goes without saying, Bruce’s Beach would look a lot different if hate and resentment didn’t lead to its demise. Perhaps there would be an even larger seaside Black community than the one 100 years ago. A community with not only Black residences but Black businesses as well. Maybe the wooden trestles that lined the beach in the past would be cabanas today. Surely we would have a bigger presence. Now, there aren’t any remnants of the Black beach community that once was: the City of Manhattan Beach currently has an estimated population of 35,500 with a Black populace of 0.5%. In other words, visiting Bruce’s Beach now warrants a quick game of “count the Black people.”

The Bruce’s Beach of today, and many former Black beaches throughout our country, lack strong Black community ties. Our sense of ownership and connection to the landscape was interrupted, but who is to say the beach can’t one day be a part of Black culture at large? For those of us who cannot swim, throwing a frisbee, catching a football or passing a volleyball are fun alternative activities. One of the beautiful things about our versatile hair is that protective styles are perfect for the beach. Braided buns, bantu knots, twists – there are quite a few options. The beach itself hasn’t changed. It is still a temporary escape from the troubles that life brings. It is still a place of recreation and relaxation. It is still a space to create memories. Historically, others have limited our access to many public spaces. There is no need to limit ourselves to the great things the seaside offers. Though we may not often see ourselves there, we still belong. We must know and acknowledge our history to preserve and expand on what remains. Soak it up.